#102: Three Things that got me thinking

👩🏽⚕️Career moves + 🏅Duolingo wildness + 📜 motivation history

Bonjour tout le monde!

A warm welcome to the subscribers who joined us after my interview with the wise Amy Edmondson about psychological safety. (This has been my most popular piece so far! Click here or below to read or listen to it:)

If you’re new to Why Would Anyone, I hope you’ll like it here! I usually alternate between Three Things posts (like today) and essays or interviews exploring why we do the things we do.

For now, here are Three Things that made me think about intrinsic motivation in the past week:

Complex career decisions

Gamification misuse

Ken Sheldon’s book

1. What will it take?

In this opinion article, titled “Why women say no to leadership positions” and published in Frontiers in Pediatrics some weeks ago, a US physician writes about the importance of understanding the values and deep motivations of potential recruits for leadership positions.

Tessie W. October’s comments apply also beyond paediatrics and academia:

When I chatted with a recruiter, she asked, “What will it take for me to move you?” I responded, “The question you should be asking is what motivates me?” She then asked and I responded: “Anything I do has to validate my role as a good mother. Secondly, I am motivated by purpose, not fame, not money, not power.”

She also lists some of the many practical questions that will influence career moves:

Is there a strong swim team? How long will it take to travel to my parents in an emergency? Will we find a French-speaking nanny? And as a woman of color an extra layer of questions arise around safety. Can my son walk in this neighborhood wearing a hoodie? If I do not know the answers to these questions and the hundreds of other questions playing out in my head, I cannot decide if this job is the right fit.

Hat tip: my friend Jessica Wilen’s newsletter A Cup of Ambition.

2. No-learning zone

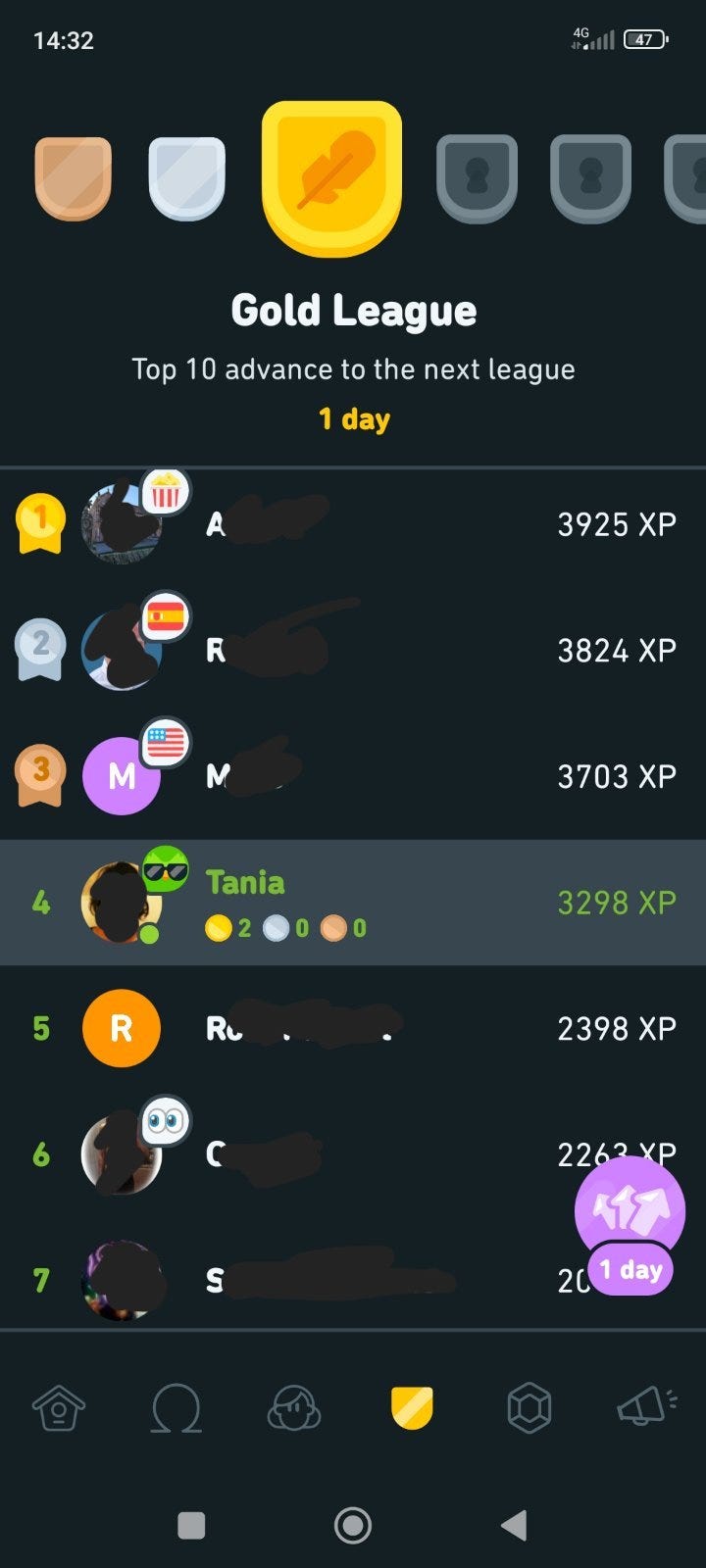

In May, I wrote about my troubled relationship with the gamified language learning app Duolingo. (I’ve since removed the addictive app from my phone, and only remember random Greek words.)

Two days ago, I was shocked to learn that some people reach insane levels of cheating at Duolingo (aren’t I naïve?) in the latest issue of Caitlin Dewey’s newsletter Links I Would Gchat You If We Were Friends. She wrote about the phenomenon of “XP farming”—playing the game only to accumulate points that have no value outside the app—and mentioned an (as-yet non-peer-reviewed) study by researchers at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. The researchers say:

Gamification misuse is a phenomenon that occurs when users become too fixated on gamification and get distracted from learning. This undesirable phenomenon wastes users’ precious time and negatively impacts their learning performance.

The researchers identify different reasons behind gamification misuse:

active ones—i.e. the gamers’ own “competitiveness, overindulgence in playfulness, and [drive to challenge] the system” and

passive ones—i.e. app features that “indirectly manipulate” users: “dark nudges of gamification, compulsion, and herding”.

This all makes me feel vindicated about my gripes with the app, or possibly with gamification more broadly. And also, isn’t this fake learning sad and infuriating? Dewey writes:

It’s also hard to miss the fact, however, that these features are working exactly as intended. In Duolingo’s most recent shareholder letter, CEO Luis von Ahn described several of the app’s gamification features as plays to boost revenue and engagement. Incidentally, the number of paid Duolingo subscribers was up 71 percent [!] from a year earlier.

[…]

“If your goal is to learn a language in the most efficient way possible, you’d be better off using something other than DuoLingo,” one short-lived Duolinguist wrote. “And if your goal is to have fun gaming, then you’d be better off finding a game more fun than duolingo.”

3. Curious cats

You may have seen me quoting the work of Ken Sheldon, a psychology researcher at the University of Missouri, for instance on the motivations of long-distance hikers and on materialism around Christmas time. He’s just released a pop psych book titled Freely Determined: What the New Psychology of the Self Teaches Us about How to Live, which I’m excited to read.

This excerpt published by Lit Hub is a good primer on the history of self-determination theory, “the world’s most comprehensive and best-supported theory of human motivation,” how it emerged in the late 1960s, and how it contrasts with other theories of human motivation:

Today, the concept of intrinsic motivation is almost1 universally accepted, and it is easily seen even in nonhuman animals (just search for “curious cats” on YouTube). The bigger the brain, the more intrinsic motivation it has—the more it “plays.”

But in the 1960s, intrinsic motivation was a radical idea. Psychologists through the 1950s and into the 1960s (before the so-called cognitive revolution) were not comfortable with the idea that people “moved themselves” or “directed themselves.”

The real causes of our behavior, according to the drive and behaviorist theories of the 1940s and 1950s, had to be some combination of physical factors (one’s biological drives) and historical factors (one’s conditioning). […] A hungry undergraduate keeps returning to a particular snack machine for food, and an underwater swimmer keeps returning to the surface for air.

Today, we know that intrinsic motivation is a real thing and that it is really important. Self-directed exploration and play are primary factors in human learning and development. Our curiosity, more than anything else, is what promotes deep and lasting learning, not the grades or the praise we receive.

My next post on Wednesday will sum up what I’ve learnt in the past year of writing this newsletter with the support of the Attuned writer fellowship. See you then, and subscribe if you don’t already:

Some psychologists, also today, do dismiss the concept and consider that intrinsic motivation derives from extrinsic reinforcement or punishment. See for instance this short video (in Spanish) by Ricardo de Pascual. Psychology researcher Stefano Di Domenico also touched on those different takes in our interview about neurobiological research and intrinsic motivation.