#39: Why Would Anyone study intrinsic motivation in the brain?

🧠 A Q&A with psychology and motivation researcher Stefano Di Domenico

Geeky reader, you’re in for a treat if—like me—you’re curious about the neurobiology of intrinsic motivation. What do neuroscientists know about intrinsic motivation? Is it a real thing that we can see in brain imaging studies? What does it mean?

It turns out that there isn’t much research in this area yet. In 2017, Di Domenico, now an assistant professor in psychology at the University of Toronto Scarborough, Canada, reviewed the emerging body of research in that field, calling it a “new frontier in self-determination research”. A neuroscience of intrinsic motivation “promises new insights that introspective and behavioral methods alone cannot afford,” he wrote.

In other words, looking at people’s brains gives us more information than just asking them what they’re thinking, or observing what they’re doing.

Di Domenico kindly agreed to explain what that means in more detail. What follows is a transcript of our conversation, edited for brevity and clarity. (We spoke for an hour, so this is considerably shortened!)

What’s the main message from your review?

I think the most important point is that humans have a capacity for intrinsic motivation, and other animals have a capacity for intrinsic motivation. People play with their dogs, and they know when their dog wants to play. It's part of our mammalian heritage.

One school of thought, which has been very influential on me, says that humans and other mammals have this brain circuitry that keeps them in a state of exploratory engagement with the world. Animals need [...] to find food, shelter, nesting sites, mates, etc. The world is complex and it’s always changing, so it’s useful to be motivated to explore it. Intrinsic motivation has evolutionary significance.

We humans, because we have this more sophisticated brain, get to also explore abstract environments. We explore through philosophy and science and [...] art. And often, these activities are pursued and enjoyed through intrinsic motivation.

There is a lot of psychology research with children, who seem to experience the purest kind of intrinsic motivation. Is that related to the way the brain develops from childhood to adulthood?

That's a really good question. I'm unaware of any research that has directly examined that. My suspicion is that if intrinsic motivation is more prominent in children, it’s because so much more of the world is new to them, so they have a lot more to be curious about—like what happens to us adults when we travel, see new places, meet new people, or learn about new topics.

In popular science writing, I see a tendency to use, or misuse neurobiology to justify certain behaviours as desirable or harmful—in parenting books for instance.

We have to be very careful in the way we marshal information and science to solve real-world problems. I think the most practical point of my paper for an educator is that there appears to be a system in the brain that regulates intrinsic motivation. It's really there, and there are instances where we want to nourish that.

Intrinsic motivation does seem to be associated with better learning, deeper learning, more positive feeling; it's often described as being an optimal experience. We all have that capacity. And so there may be certain contexts, like educational contexts for example, where we want to have that system going as much as possible.

Why is it important to study what’s going on in the brain to understand intrinsic motivation?

Our behaviour and experience is mediated by the brain. So we can't understand our behaviour or experience completely if we don't have some model of how it happens in the brain.

The other value is that when you try to map experience to the brain, you find multiple systems related to intrinsic motivation and your understanding of how it works can become more refined. That could lead researchers to ask different questions. And it’s a two-way street: if you have a model at the experiential level, you might be able to articulate a model at the level of the brain, then that model may in turn inform your understanding of the experiential level.

You write that, according to existing studies, intrinsic motivation is supported by dopaminergic systems in the brain. What does that mean?

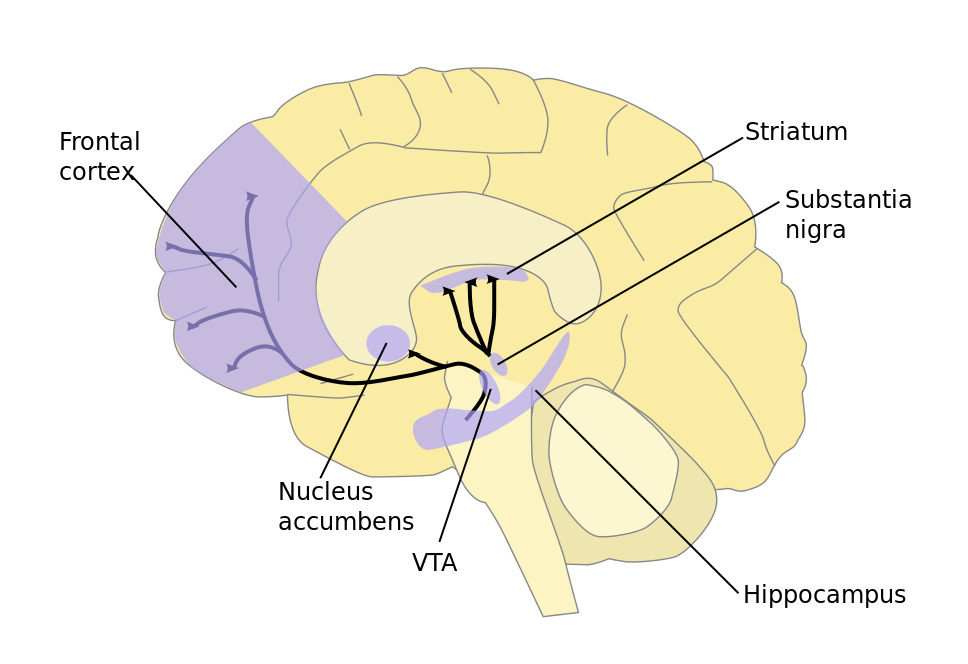

There are cells in the brain, neurons, that communicate with other cells primarily through dopamine. In studies using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, for example, we see these regions of the brain–that we know are rich in dopamine receptors–to be active during intrinsic motivation. I’m referring to structures deep in the brain, the ventral tegmental area [VTA] and the substantia nigra, that have connections with other regions “higher up” in the brain like the striatum and other parts of the cortex.

You also write that intrinsic motivation entails “dynamic switching between brain networks for salience detection, attentional control and self-referential cognition”. Could you explain that?

Some neuroscientists are interested in understanding how individual neurons code information and respond to certain events. Other neuroscientists are interested in the chemicals that the neurons use. Of course, these are overlapping areas of study. But the point is that the brain can be examined at different levels of analysis.

Zooming out, some neuroscientists are interested in understanding how different brain regions work together to orchestrate some behaviour. There are large-scale networks in the brain that seem to be reliably associated with different types of cognitive tasks. The network for self-referential cognition, which is active when people think about themselves or when they daydream, tends to be less active when people have their attention focused on some task, like when they are immersed in solving a puzzle. And this type of outwardly focused attention seems to be mediated by its own network. We say there’s an “antagonistic” relationship between the activity in these networks.

It looks like intrinsic motivation involves shifting between networks. When people are intrinsically motivated, they're absorbed in a task, so they’re using attentional resources. And they're not self-conscious, not worried about the way they look or sound. So we see the subjective experience of intrinsic motivation mapping quite well to what we know about the operation of these two brain networks.

Your paper says there had been little research in the field of neuroscience of intrinsic motivation until recently, and I’m curious to know why.

It's often studied, but with different names. Back in the 1950s, [psychologist Harry] Harlow found that if you have primates in a cage, they'll play around with a mechanical puzzle, they'll explore; that looks intrinsically motivated. In fact, he coined the term intrinsic motivation. Comparative neurobiologists, for example, those who study rat brains, made progress in identifying some specific neural circuits that seem to drive that exploration.

In social psychology, a lot of the work on intrinsic motivation in humans is being done within the framework of self-determination theory. It has the most articulate and well-developed model of intrinsic motivation, in my opinion1.

There are also personality psychologists who study intrinsic motivation, but who don’t often use the term “intrinsic motivation”; they call it interest, or creativity, or curiosity. And they measure it not as a state of behaviour and experience that happens in a particular situation, but as a personality trait: “Some people are more curious on average than others”. I should also say that in artificial intelligence research, there are computer scientists and roboticists who have taken an interest in intrinsic motivation, because their goal is to develop robots that are capable of exploring environments on their own.

Something I was trying to show is that all these researchers are talking about the same thing. Or, at the very least, they're talking about different things that overlap with one another to a high degree. One of the goals of that [2017] paper was to consolidate all that information, all that work.

So it's not that the neuroscience of intrinsic motivation wasn't studied, it’s just that people didn't really call it that?

Let’s say intrinsic motivation isn't a topic that's widely researched within the neurosciences, but there's growing interest in it. Most neuroscientists adopt what we might call a neo-behaviourist point of view.

What does that mean?

In the past, behaviourists dismissed the very notion of intrinsic motivation; they weren’t interested in subjective experience, but focused on behaviours that we can observe from the outside, which they see as a function of the animal’s environmental conditioning. A lot of the terminology that contemporary neuroscientists use, including terms like “reward,” has been imported from behaviourism.

Let’s make this concrete. Let’s say you’re working on a puzzle. You’re trying to put the pieces together. You try different ones. Sometimes they fit, sometimes they don’t. If it’s a fun puzzle, a puzzle you’re intrinsically motivated to complete, it’s a challenging task, not too easy, and your attempts at fitting the pieces fail from time to time. Well, from neuroscience studies, we know that’s the exact type of situation that fires up the dopamine neurons in what neuroscientists call the “reward system.” So maybe it’s not exactly a “reward system” in the way behaviourists think.

Now, a behaviourist might say: Well, the perception of the pieces of the puzzle fitting is an “internal reward.” But an intrinsic motivation researcher would say: Hold on. That doesn’t match the definition of a reward2. In the strictest sense, you can't be a behaviourist and then speak of internal rewards to explain away intrinsic motivation. “Internal rewards” are a theoretically deep contradiction. So some neuroscientists don’t have a well-developed framework for researching intrinsic motivation.

Anything you’d like to add?

As important as intrinsic motivation is for people's sense of well-being, it's not the only healthy way to be motivated. Sometimes there's work to be done that's important, but not necessarily fun or intrinsically motivated. That could still be done in a volitional way, in a way where people don't feel pressured or forced into it.

Cultivating that, having an environment that supports that is really important—not only for personal maturity, but also if you're running an organisation or a classroom. If people understand why an activity is important, if they can identify with the underlying rationale for it, if they can consent to it, then the quality of engagement can be quite good.

According to behaviourist theory, rewards or “positive reinforcers” are externally specifiable, measurable stimuli that increase the probability that a specific behaviour will be performed in the future.

Wow, Tania, this was awesome! Great job.

SDT: A Contrarian take from Affective Neuroscience, or a 'radical' behaviorism

Although the metaphorical reality of need states and intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is accepted in personality psychology and allied disciplines such as social psychology and economics, in learning theory, it is not. Indeed, modern neurologically grounded learning or incentive motivation theory has long abandoned concepts of need or drive, and unified theories of reinforcement of reward reject the bifurcation of motivation into intrinsic/extrinsic, operant/respondent, voluntary/involuntary processes in favor of single process models which can explain all behavior with readily testable predictions.

The position is epitomized by the research of the distinguished learning theorist and affective neuroscientist Kent Berridge of the University of Michigan, whose article on reward learning is linked below. Also linked below is my version of this article and its practical implications for a lay audience, reviewed and endorsed by Dr. Berridge in its preface. A precis of my argument is on pp. 57-63.

‘A Mouse’s Tale’ Incentive motivation theory for a lay audience from the perspective of modern affective neuroscience https://www.scribd.com/document/495438436/A-Mouse-s-Tale-a-practical-explanation-and-handbook-of-motivation-from-the-perspective-of-a-humble-creature

Berridge article on history of learning theory https://www.scribd.com/document/447163649/Berridge-Reward-Learning-Incentives-and-Expectations

Berridge Lab, University of Michigan https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/berridge-lab/