#53: Three Things that got me thinking

💯mediocrity + 🔫 mass shootings + 🎭 bipolar disorder

Bonjour,

Today’s themes are both dark and hopeful, which is apt on this Katzenjammer Monday.

I did try to find cheerful things to write about. But writing this newsletter is teaching me to trust my own motivation radar: if I’m drawn to these subjects, then let’s look at them properly.

1. Nowhere special

In this recent Ask Polly advice column1, a letter writer says her life looks like a dream—job, kids, house, alive after a long illness!—but feels mediocre and “just okay”. Can you relate?

Sometimes I feel like a casualty of those elementary school motivational posters: Shoot for the moon and you will land among the stars! I don’t feel like I reached the moon or the stars.

Polly/Havrilesky replies2: [replace “writing” by programming / baking / building, or whatever floats your intrinsic boat]

Real happiness requires a tightrope walk between accepting the imperfection of what you have and savoring the deliciousness of wanting more. For me, the kind of wanting that’s delicious is more sensual and less ego-driven: I want a life that feels romantic, poetic, sublime. I get there through my writing.

It does take work. But it doesn’t take *motivation.* Because I crave the work itself. I don’t want to arrive somewhere special.

Maybe it doesn’t take motivation, if you think of motivation as finite gold dust that you must seek outside yourself, to push or pull you forward. But the work, the discovery, the wanting: to me, that is motivation.

2. Why mass shooters kill

I discovered the Violence Project (a research centre funded by an agency of the United States Department of Justice) in a recent post about the epidemiology of mass shootings by Katelyn Jetelina, an epidemiologist who usually focusses her data-packed newsletter on COVID-19.

The Violence Project’s database3 includes information about 172 mass shooters in the U.S. between 1966 and 2020—including, among other variables, the killer’s education, the guns they used, their mental health and, you guessed it, their motivations.

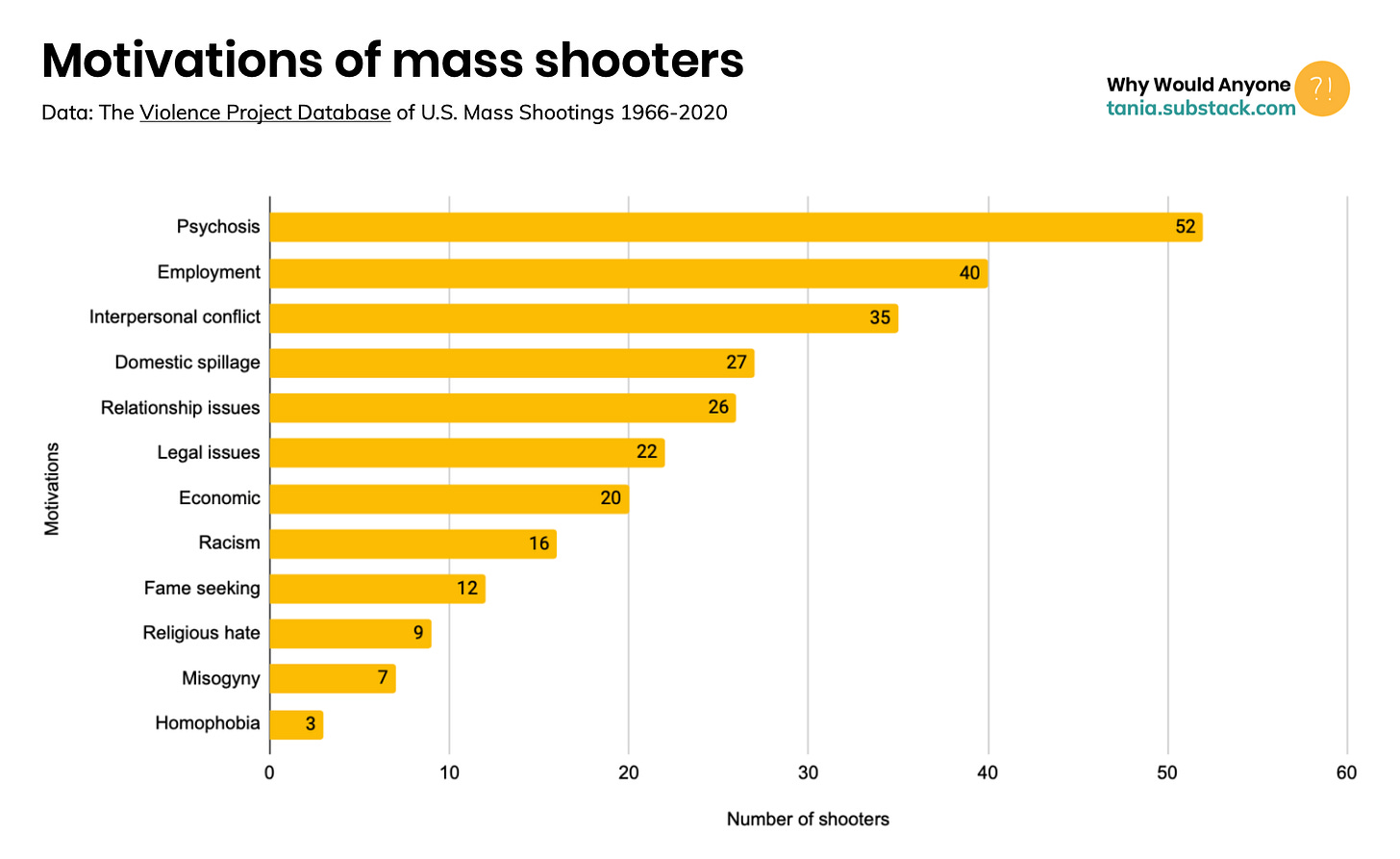

The most common known motives in those records—besides psychosis—have to do with personal issues in the shooter’s life: job issues, conflicts, relationship problems4.

The most common motivation at 30% is psychosis, a mental condition that makes it difficult for a person to recognize what is real and what isn’t. That is followed by followed by employment troubles (23%) and interpersonal conflict (20%), defined as a non-domestic conflict with coworkers, friends or family.

Fame-seeking and hate (racism, religious hate, misogyny, homophobia) are at the bottom of the list, BUT have been rising in recent years:

I’m glad somebody is doing this work (and getting funding for it), lest we dismiss mass killings are inexplicable, isolated cases. As Jetelina says:

On the surface, mass shootings, and violence in general, seem random. But if researchers can uncover patterns, then they’re predictable. And if they’re predictable, they’re preventable.

3. Motivation disorders

Would you climb five flights of stairs to eat your favourite meal? Ten? Thirty? (As I write this, I reckon I’d climb 15 to eat a creamy avocado gratin from my childhood.)

Researchers at the Paris Brain Institute of the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital study what happens in our brain when we make such cost/benefit analyses—and when a person has a disease in which “motivation is deficient or uncontrollable”.

For instance, in the case of bipolar disorder:

During a manic period, the costs of a decision [the stairs] are under-estimated while the value of the reward [the meal] is overestimated. And the opposite happens during depressive periods.

The quote above comes from a 6-minute radio package5, broadcast last month on French public radio France Inter, about the work of Matthias Pessiglione6’s research team. They come up with computational models to analyse and reproduce decision-making processes—instead of relying on patients filling up questionnaires about their motivation levels.

The idea is to put together behavioural tests to analyse the mechanisms of decision-making. These tests are very varied—it can be for instance questions like “Would you rather have 10€ now or 11€ tomorrow?” Or the subject has to grip an object to get a reward or grip it harder to get a bigger reward.

In parallel, the researchers use brain imaging to understand what brain areas are activated when people make those decisions. So far, their approach seems to help understand motivation deficits (or excesses) and could help personalise treatment. For example:

the model seems to detect mood fluctuations that predict a shift towards a manic or depressive episode.

I’d like to look into this research in more detail—would you be interested in finding out more?

This is from Ask Polly’s About page here on Substack—a mission statement that resonates with what I’m (humbly) trying to do here:

Your happiness doesn’t depend on unlocking a new levels of success, status, wealth, fame, beauty, and adventure. We weren’t built to chase empty goals through infinite mazes, satisfaction always eluding us. We’re here to savor the conflicted, melancholy pleasures of each day. Our joy depends on embracing our imperfect selves as we are, treasuring the impermanent wonders of this moment, and fighting to make the world a more just and habitable place for everyone.

Polly also says: “there is no way on earth to be anything but mediocre when you have two toddlers in your house”. Why, thank you!

The team collected more than 100 pieces of information on each of 172 mass shooters in the United States between 1966 and February 2020. They used the Congressional Research Service’s definition of a mass shooting: “a multiple homicide incident in which four or more victims are murdered with firearms — not including the offender(s) — within one event, and at least some of the murders occurred in a public location or locations in close geographical proximity (e.g., a workplace, school, restaurant, or other public settings), and the murders are not attributable to any other underlying criminal activity or commonplace circumstance (armed robbery, criminal competition, insurance fraud, argument, or romantic triangle).”

Thanks D. for the tip 🐬

That first point is going to stick with me for awhile. In a culture that encourages one to be excellent, what happens when we aren’t. Dealing with this in a real way as my sons prove very middling athletes.